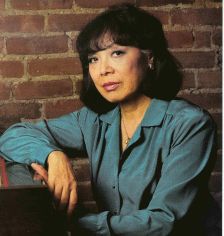

Toshiko Akiyoshi (1926 -- ) jazz pianist, big-band composer and band leader Photo at right by Tsutomo Far right: Toshiko conducts her big band at the 1976 Monterey Jazz Festival. |   |   |

Hear Toshiko play jazz piano: Notorious Traveler from the East, Toshiko Akiyoshi Trio |

1929 -- 1946: From riches to rags |

U.S. concentration camps |

The youngest child of upper-class Japanese parents, Toshiko Akiyoshi grew up in Darien, Manchuria, a part of mainland China then ruled by Japan. Her father, a textile and steel mill owner, was also well-versed in Japanese Noh drama. As part of their upper-class education, he had his four daughters study traditional Japanese dance, classical ballet and piano. Toshiko's study of Western classical music began at the age of seven with piano lessons. She fell in love with the instrument and soon dropped out of her ballet and Japanese dance classes. [1] The youngest of four daughters, Toshiko said her father, disappointed at not having a son, expected her to achieve great success, not as a musician but as a doctor. World War Two changed that. When the war ended in 1946, the Akiyoshi family was deported to Japan, penniless, carrying only what fit into their suitcases. Toshiko was seventeen years old. [3] | After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 and won control of Guam, Hong Kong, and Manila, many believed their mext target would be the United States. Living in the U.S. in 1941 were 125,000 men, women and children of Japanese birth or descent. Less than 1% of the population; more than 60% of them were U.S. citizens. Many (Issei) had come to the U.S. decades earlier and clung to their native language and customs. But their children (Nisei) had attended U.S. public schools and most had the same tastes as their Caucasian peers. In 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt signed an order forcing 120,000 Japanese-Americans into internment camps. No charges were made against them, and no hearings were held to find evidence of subversion. Families lived in barracks with no partitions, stoves or running water; 300 people shared a mess hall, laundry, latrines and showers; 30,000 children attended school in the camps. [2, 4, 7] |

1946 - 1950: Post-war Japan

| Military Occupation of Japan |

The family settled in Beppo City in southern Japan, a city heavily occupied by U.S. soldiers. Toshiko desperately missed her piano. One day she saw a sign in the window of a dance hall used to entertain U.S. soldiers: Pianist Wanted. She spoke to the manager, who said he needed a pianist for the dance band. She knew nothing about dance music. To audition for the job, she played a Beethoven piano sonata. Impressed, the manager told her to begin at six that night. The band, led by an ex-Navy orchestra leader, consisted of a violin, saxophone, accordion, drums, and Toshiko on piano. Toshiko hated the dance-band arrangements, but loved having access to a piano. Her family knew nothing about her new job. When they found out, it caused a huge argument. Her father finally agreed to allow her to keep the job, but only until she began medical school. [3] In the afternoons she practiced classical repertoire on the club’s piano and dreamed of a music career. One night a Japanese record collector heard her play and told her she had the potential to become a great jazz pianist. Later, he played a recording of American jazz pianist Teddy Wilson for her. Wilson’s rendition of “Sweet Lorraine” was a revelation. “When I heard it,” she later said, “I knew I wanted to play like that.” [5] Enthralled by American jazz, she spent hours copying music from recordings and began writing her own. In 1950, against her family's wishes, she left Beppo City and moved to Tokyo. | General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Allied Powers, oversaw the occupation of Japan. Early in 1946, demobilization of all Japanese military forces was complete, but Japanese citizens faced desperate conditions. Firebombing had destroyed the wood-frame homes most had occupied; only concrete buildings remained. Thousands of Japanese families lived in railroad stations and public parks. Food was scarce, especially fish, a staple of the Japanese diet, because Japan’s fishing fleet had been decimated. Former President Herbert Hoover headed a committee that recommended 800-million tons of food be sent to Japan and distributed in urban areas. [6] During WW II, 20,000 Japanese American men and women served with distinction in the U.S. Army. In 1946 the last Japanese American internment camps in the United States were closed. [7] Although many Nisei set aside their bitterness and returned to life as U.S. citizens, life was difficult for the older generation. Their old communities and livelihoods were gone. After four years in the internment camps, they felt only despair. [4] |

1950s: Recognition, of sorts

| Repatriation and Reparations |

In Tokyo she formed her own group and studied improvisation by listening to recordings by Teddy Wilson and Bud Powell, a be-bop pioneer in the 1940s, who became her biggest influence. Her big break came in 1953. Jazz pianist Oscar Peterson was in Japan to play a “Jazz at the Philharmonic” concert produced by Norman Granz. Peterson heard Toshiko play and urged Granz to record her. The recording, Toshiko’s Piano, was an overnight success in the States. By 1955 she was Japan’s leading jazz pianist; soon she was the highest paid jazz musician in Japan. [1, 3] But she said, “I knew that I had to come to the States to [improve] as a jazz player.” She applied to Berklee College of Music in Boston and included a copy of Toshiko’s Piano. Berklee president Lawrence Berk immediately recognized her talent and offered her a full scholarship and a plane ticket to Boston. [8] | In 1951 Japan, the United States and 47 other nations signed a peace treaty. The treaty took effect in April 1952, officially ending the U.S. military occupation and restoring full independence to Japan.

Under the new Japanese Constitution, women had full equality with men, giving them equal rights long before women in the U.S. achieved this. In 1968, the U.S. government began paying reparations to Japanese Americans for the property they had lost when they were sent to the internment camps. However, by this time, many of them had died. In 1988, the U.S. Congress awarded $20,000 to each of the 60,000 surviving internees. [6] |

She began her first semester at Berklee in January 1956. One night she sat in with Bud Powell’s trio at Storyville, a nightclub owned by jazz producer George Wein. Two months later she was playing there four nights a week; that summer she performed at the Newport Jazz Festival. [8] But much of the attention she drew was based upon her race and gender. In one instance, she appeared on the TV show “What’s My Line,” playing be-bop piano in a Japanese kimono. Photo at right. Watch a film clip from 1958: Toshiko Akiyoshi Trio A 1957 Time Magazine article touted her playing as “some of the best jazz piano around” but a press agent told her she should wear a kimono all the time because she was “the only female jazz pianist from Japan.” [9 ] |   |

In 1950, only 5 million U.S. homes had TV; by 1955 that number had soared to 55 million. People watched Elvis Presley on TV. Rock began to dominate popular music, and the popularity of big bands and jazz declined. In the late 1950s, Toshiko began a relationship with Charlie Mariano, a saxophoist who had played with Stan Kenton. In 1959 they married and formed the Toshiko-Mariano Quartet. | |

1960s: Hard times on two continents

|

For much of the 1960s, Toshiko divided her time between Tokyo and NYC, touring Japan and Europe with small jazz combos. In 1964 Charles Mingus featured her with his band in a Town Hall concert. Although she won critical acclaim and her talent was recognized by top jazz musicians like Mingus, John Coltrane and Art Blakey, she remained on fringes of jazz. [10] In 1964 her daughter, Michiru Mariano, was born in Japan, but in 1967 her marriage to Charlie Mariano ended. She played solo piano gigs at NYC jazz clubs, but later said, “It was hard to be a single mother supporting myself as a jazz musician.” [10] Her compositional interests turned to big band. “I wanted to hear more colors," she said, "in order to express my musical and philosophical attitudes through jazz language.” [5] |   |

A Nat Hentoff article in the Village Voice also inspired her. "[Hentoff] talked about how proud Duke Ellington was about his race, and so much of his music is based on his heritage. When I read that, I said, that’s what I should be doing." [8] She began to add Japanese elements to her music. To draw attention to her big band compositions she decided to give a concert in Town Hall. To finance it she went door-to-door to solicit money from the Japanese business community in NYC. “They will only buy if I come to them in person," she said. "I spent many days going to businessmen (to sell tickets) and nights working on my music. It is very tiring, but it must be done this way. Otherwise it is not proper.” [3-A] Her 1967 Town Hall concert was a critical success, but the cost of rehearsing and performing with a big band limited her ability to develop her big band writing skills. Then her life took another turn. She met saxophonist Lew Tabackin, who recognized her potential and encouraged her to continue writing. In 1969 they were married. | |

The 1970s: Acclaimed recordings ... in Japan |

In 1972 they moved to Los Angeles and Tabackin joined Doc Severinson’s band on The Tonight Show. The couple organized a “workshop” big band that rehearsed weekly, and Toshiko’s portfolio of big band charts grew larger. A year later they were hired to play at a small club in Pasadena, but their meager pay consisted of the door receipts. They financed a concert in Los Angeles and drew a large audience, but producers and club owners wanted smaller, less expensive ensembles. Toshiko again turned to the Japanese community for financial backing to record the band in a small studio in L.A. in 1974. |   |

KOGUN |

With its blend of Japanese traditional instruments and big band jazz, Kogun was unique. Released only in Japan, the album became one of Japan’s biggest all-time jazz hits, selling thirty-thousand copies upon release and tens of thousands more thereafter. The title track, Kogun, (loosely translated: One man army) was inspired by a news article Toshiko had read: a Japanese soldier had been discovered hiding in a cave in the Philippines, believing that World War II had not yet ended. The soldier finally emerged from the cave and surrendered his sword. [3] Listen to this amazing composition: KOGUN | |

Kogun and subsequent recordings cemented her reputation as a big band composer-arranger-conductor. The Akiyoshi-Tabackin Big Band placed first in a Downbeat critics’ poll in 1976; Long Yellow Road was named best album of year by Stereo Review Magazine; Insights was voted Jazz Album of the Year in Japan. Since 1976 Toshiko's big band albums have received 14 Grammy nominations. At right: Toshiko conducts the band; Lew Tabackin solos on saxophone. |   |

For the first time in the history of jazz, in 1978 a woman received top honors in the categories of jazz, composer-arranger and big band. Downbeat’s critics selected Insights as Record of the Year, Toshiko won first place as jazz arranger, and her band was voted number one. By 1980 the Toshiko Akiyoshi – Lew Tabakin Big Band was considered one of most important big bands in jazz. |

The 1980s-90s: Critical success, financial struggle |

After Tabackin left the Tonight Show band in 1982, the couple moved to NYC and formed a new band: the Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra featuring Lew Tabackin. But Toshiko still had to tour with small combos or play solo piano gigs to raise money for the band. The band recordings were big hits in Japan, but available only as imports in the U.S., where the only albums available featured Toshiko on solo piano or in small combos. |

2000: A new century, a new piece, new directions |

In 1999 a Buddhist priest asked her to compose a piece for Hiroshima and sent her photos taken three days after the atomic bomb was dropped. “The photos were so awful,” she said, “people losing skin and so on. ... I had never seen anything like this ... I really didn’t see the meaning of writing about something so tragic and so horrible.” But then she found one photo she hadn’t noticed before, “a woman who was underground and wasn’t affected by the bomb and . . . this photo was beautiful.” The woman’s faint smile of hope inspired her. [8] Her three-part suite, Hiroshima: Rising From the Abyss, had its premier in Hiroshima on August 6, 2001, the 56th anniversary of the bombing and only weeks before Sept 11, 2001 attacks on U.S. “It was an emotional concert,” she said. “Some musicians told me how proud they were to be associated with the organization. It was a great performance. I actually cried on the stage because Lew (her husband) plays so beautifully on the last [piece].” [8] |

In December 2003 her band played its last concert at Birdland in New York, where it had played every Monday night for more than 7 years. She found it discouraging that the band's recordings remained popular in Japan but were available only as imports in the U.S. And, after being away from it for almost 30 years, she wanted to get back to her first love, piano. Although she often soloed with the band, she said it wasn't the same. “I’m 74 years old," she said. "I think I can get better. ... That’s the wonderful thing about jazz. There is no end. There is always something to perfect.” [11] | |

In 2007 Toshiko's extraordinary talent and multi-faceted career won recognition from the National Endowment for the Arts, which deemed her a Jazz Master, its highest honor in jazz. Of the six honorees, she was the only woman. Photo at right: awards ceremony in New York, January 2008. Toshiko and her husband Lew Tabackin currently live in New York City. |   |

COMMENTARY MUSICAL INFLUENCE: Be-bop pianist Bud Powell. "People used to call me the female Bud Powell. ... That's how I learned in Japan, by copying his solos off records. ... After a while I realized I had to develop my own style, but Bud is always with me, especially his rhythmic approach." [12] MENTORS: Charles Mingus, Oscar Peterson, Norman Granz, George Wein, and most importantly, her two husbands, Charlie Mariano, and Lew Tabackin, who encouraged her and provided entre into the male jazz world and with whom she collaborated. RACE & GENDER ISSUES: Although her gender and race drew media attention, they also held her back. Despite recognition of her talent by her (male) peers and many jazz critics, for many years she did not receive the credit she deserved. Her big band recordings were released in Japan, but not in the U.S., preventing the band (and her) from gaining wider fame and gigs which might have alleviated the constant financial concerns.

HER LEGACY: Her albums as piano soloist and with small groups. Her big band charts and recordings. Her keen intelligence, musical talent and dogged determination led to her ultimate success. Even as a single mother, she continued to work. The first woman to compose an entire "book" for a big band, she received 14 Grammy nominations, and, in 2007, the jazz world's highest award when the NEA named her a Jazz Master. Her Daughter: Born in 1963, Japanese American actress, singer-songwriter, best known as Monday Michiru. After playing a lead role in the Japanese movie "Hikaru Onna," she won several Best New Actress awards. Thereafter, she appeared on several TV networks. In 1991 she released her debut solo album "Mangetsu" and became a singer/songwriter for other groups and artists. Since then she has released more than 12 albums. She now lives in New York City with her husband, jazz trumpeter Alex Sipiagin and their son Nikita. [13] |

Watch the Toshiko Akiyoshi Big band (1996): Dance of the Gremlins DISCOGRAPHY Toshiko appeared on more than 75 recordings (1953 – present); These are a few highlights. [Note: different record labels sometimes used similar titles for different albums] As Leader or co-leader: Toshiko’s Piano (1953); also released as Amazing Toshiko Akiyoshi The Toshiko Trio – George Wein Presents Toshiko (1956) The Toshiko – Mariano Quartet (1960) Lullabies for You (1965) aka Toshiko’s Lullabies Toshiko Akiyoshi: Solo Piano (1971) Toshiko Plays Billy Strayhorn (1978) Remembering Bud: Cleopatra’s Dream (1990)

Toshiko Akiyoshi – Lew Tabackin Big Band (1974 -- 1982) Kogun (1974); Long Yellow Road (1975); Live at Newport ’77 (1977) From Toshiko with Love (1981) Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra featuring Lew Tabackin (1984—2003) Carnegie Hall Concert (1991); Hiroshima – Rising from the Abyss (2001) Last Live in Blue Note Tokyo (2003) Big Band Compilations; inclusion in other compilations The Best of Toshiko Akiyoshi (BMG/Victor) The Music of Duke Ellington: Jazz Piano Essentials (2000, Concord) The Best of Newport ’57: 50th Anniversary Collection (2007, Verve)

Featured pianist: Charles Mingus: The Town Hall Concert (1963; United Artists); Expanded re-issue The Complete Town Hall Concert (1994, Blue Note)

Video Recordings: My Elegy (1984); Strive for Jive (c. 1985) Appearances on other videos: Monterey Jazz Festival 1975 (2007 Storyville Films) Jazz Is My Native Language (c. 1982 documentary)

Autobiography: In 1996, Toshiko published her autobiography, Life With Jazz |

SOURCES: Toshiko Akiyoshi profile 1. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen, Linda Dahl, 1984

3. “Toshiko Akiyoshi: Jazz Composer, Arranger, Pianist, and Conductor,” Laura Koplewitz, in The Musical Woman, Volume II (1984-1985) 3-A. "Jazz is Her Way of Life," Bryna Taubman, NY Post, 4 Oct. 1967, quoted by Koplewitz

5. “The First Lady of Jazz: An Interview with Toshiko Akiyoshi,” Matt Weiers, Allegro, an AFM Local 802 publication (NYC), Volume CIV No.3, March 2004 8. AllAboutJazz.com: "A Fireside Chat with Toshiko Akiyoshi”, Fred Jung, 2003

9. Time Magazine, “Jazz Import,” August 26, 1957 10. Berklee Today, “Toshiko’s Odyssey,” Mark L. Small, Spring 1993, Vol IV, No. 3 11. Berklee News, "Playing Shape," Ed Hazell, June 2, 2004 12. "A Hub homecoming for Akiyoshi," Bob Blumenthal, Boston Globe, 10-16-1992

13. Wikipedia, the free encylopedia: Monday Michiru Information on Japanese-American internment camps and post WW II Japan 2. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of American’s Concentration Camps, Michi Weglyn (1976, 1996), University of Washington Press 4. This Fabulous Century: 1940-1950, Time-Life, Vol. 5, 1969 6. Studyworld.com: American Occupation of Japan 7. infoplease.com: Japanese Relocation Centers, Ricco Villanueva Siasoco & Shmuel Ross |

© copyright 2008 Susan Fleet