|

Doriot Anthony Dwyer (1922 -- ) First woman to win a principal chair in a major U.S. orchestra Principal Flute, Boston Symphony Orchestra (1952 -- 1990)

|

| In April 2012 Doriot was inducted into the Rochester Music Hall of Fame at the age of 90. She played one movement of the Darius Milhaud Sonatine for flute & piano photo right |

|

Quote from the Rochester Music Hall website: "On April 30, 2012, fifteen hundred people filled the Eastman Theatre for the first induction ceremony of the Rochester Music Hall of Fame. It was a historic event, filled with tears, laughter, stories, and most importantly, music. One highlight of the evening: Ninety year old flutist, Doriot Anthony Dwyer, gave a deeply moving performance accompanied on piano by Cherry Tsang. Doriot was introduced by Susan Fleet, a music historian and musician, who really helped us understand the barriers that Doriot broke down by her sheer talent and determination. There were few dry eyes in the audience after this induction." |

Hear Doriot play the 3rd mvt. of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich's Flute Concerto, premier performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, April 1990 |

1922 -- 1939: FLUTISTS With ATTITUDE | 1920 Prices |

Born in Streator, Illinois, Doriot inherited her name from her maternal grandmother, Emily Doriot. Her mother, Edith Anthony, played flute in the Chicago Women’s Symphony and toured for several seasons on the Chautauqua Redpath circuit. Marriage and four children ended that. [1] Doriot later described her as prodigiously talented, with a powerful tone and a fluid technique. [1] “My mother was a great artist. She used the instrument to sing, and she had a huge, beautiful sound.” [4]

At age 8 Doriot began flute studies with her mother and listened to orchestras and operas on the radio with her three siblings. Inspired by principal flute Ernest Liegl in a Chicago Symphony broadcast, Doriot vowed to become an orchestral flutist, a dream her mother encouraged. Doriot's father disapproved of his cousin, Susan B. Anthony, photo at right, but her mother admired the famous Suffragist and told Doriot to “never put yourself down because you are a female." [1] Precociously talented at 12, Doriot in 1934 began studying with the flutist who had inspired her, Ernest Liegl. Rising at dawn for a 4-hour train ride to Chicago and a 1-hour elevated train ride to Liegl’s house, she studied with him twice each month for five years. [1] | Bread: .09/loaf Milk: .55/gallon Car: $305 Gas: .25/gallon Average Income: $1,155/year President: Warren G. Harding Constitutional amendments in 1920 gave women the right to vote, and Prohibition banned the sale of alcoholic beverages. New Classical Music: La Valse, Ravel; Miraculous Mandarin, Bartok; Pulchinella, Stravinsky. Top Books: Ulysses, James Joyce; The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton; Women in Love, D. H. Lawrence   |

1939 -- 1943: College and a Dose of Reality

|

Liegl recommended further study, but he had little reason to expect that she would ever win an orchestral position. In 1939 few major orchestras hired women other than harpists. [4] Doriot applied to the Curtis Institute of Music, but she was rejected. [1]

That summer at the Interlochen Music Camp, Howard Hanson, director of the Eastman School of Music, offered her a scholarship. At Eastman she got a preview of the music world. Four times, she auditioned to play principal flute in the school orchestra. She never won. However, she did develop sufficient skills to win the 2nd flute job with the National Symphony in Washington. [1] |

1943 – 1946: Washington, New York and Frank Sinatra |

During WW II, conductors were happy to hire women to fill positions vacated by men. Some women were forced out when the men returned from the war, but National Symphony conductor Hans Kindler said: “The women had proved themselves not only fully equal to the men, but sometimes more imaginative ... and cooperative.” [1] During her two years with the National Symphony, Doriot studied with William Kincaid, principal flute of the Philadelphia Orchestra, then considered one of the best flute teachers in the United States. She moved to New York in 1945. While awaiting a union permit to allow her to freelance, she asked Julius Baker, principal flute of the CBS Radio Orchestra, for a lesson. He declined but gave her a pass to the CBS studio to hear rehearsals and concert broadcasts, a fine learning experience. “They practiced and [rehearsed] and I [saw it] for a whole year.” [1] | |

She also played in the Paramount Theatre jazz band that accompanied Frank Sinatra. The pay was good, the level of musicianship was high, the flute parts interesting. “Sinatra was really an artist,” she said. “Good jazz singers are true artists: they never do the same thing twice.” [1]

In 1946, she played principal flute in an orchestra for a touring ballet troupe. It was gratifying artistically, but the tour folded in Dallas. Seeking better opportunities, she took a train to Los Angeles. |   |

1946-52: The Hollywood Bowl & Bruno Walter | Big changes after WW II |

Six months later she was playing lucrative jobs in recording studios, primarily because she was a fine sight-reader, a skill she credited to her experience playing new music at Eastman. She auditioned for 2nd flute in the LA Philharmonic and won, a position she held from 1946 until 1952. She studied orchestral excerpts with principal oboist, Henri de Busscher. A big break came when conductor Bruno Walter (photo below right) named her principal flute of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, a challenging job with a concert almost every night during its 13-week season. [4] Walter chose her to play principal flute in a radio orchestra similar to the NBC Symphony. The repertoire was difficult, the schedule demanding, but this gave her valuable the principal flute experience. Although she had graduated from Eastman, she said: “I considered those years in Los Angeles my ‘college’.” She learned how to practice, perform and audition effectively— skills that would soon be crucial. [1] | Emphasis shifted from production to consumption, from saving to spending, from city to suburb. Advertising led everyone to believe they could have a house in the suburbs, a new car, a good job for the husband, and well-adjusted children cared for by a full-time wife and mother. [7] During WW II women joined the labor force in large numbers, but after the war ended, some said they had become too independent. Returning (male) soldiers had priority for jobs and education. Women were expected to be keep house. The Betty Crocker Cookbook was a best-seller.   |

1952: A Big Audition |

Sexual Politics & Mixed Messages |

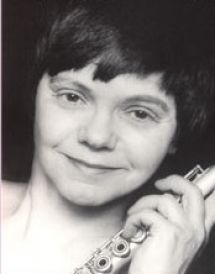

Prior to the mid-1960s orchestral jobs were rarely publicized. Many section positions were filled by pupils of the principal player. [2] But in 1952 the Boston Symphony Orchestra announced auditions to replace retiring principal flutist George Laurent. To avoid any confusion about her gender Doriot signed her application “Miss” Doriot Anthony. At that time applicants were usually male musicians invited by the conductor, but BSO conductor Charles Munch (photo right) decided to hold a “ladies day” audition. Doriot described her invitation to audition for the BSO as “the greatest thrill of my life!” [1] She went into heavy training. Here was her chance to win the job she most coveted, principal flute in a major orchestra, and she wanted to give it her best effort. For two months she practiced late into the night until she could play her audition music from memory. [1]

The audition lasted more than three hours. Pops conductor Arthur Fiedler asked for the flute solo from Grieg's Piano Concerto. Doriot played it from memory. After a while, she played everything from memory. "What do you want to hear?" she asked, "I'll just play it. ... They were knocked out by that,” she later said. [4] They asked if she planned to have children. She did, but told them it was none of their business. When they asked her to come back in two weeks and audition again, she said NO! [4] Two months later the offer came, but it said nothing about money. Told she would get the usual sum, Doriot asked for more and got it. “It’s a lot of money for a little girl,” said the BSO manager. To which Doriot firmly replied: "It's a big job." [4] | In suburbia, women and children waited for Dad to get home from work. Men were the breadwinners, pressured to support their families in style. Although teachers and parents pushed girls to pursue careers, the media showed images of housewives and issued stern warnings about careerism. [7]

Conductor Charles Munch During the 1950s, juvenile delinquency was a big problem, regarded as evidence of the family breakdown. Much of the blame went to mothers. In Rebel Without a Cause, the father of teenage rebel James Dean is afraid to stand up to his wife. Middle-class white girls loved black music and rebellious movie stars, precisely because they were forbidden. [7] They loved motorcycle-gang member Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones. Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story (1957) featured teen lovers in an urban setting: a white girl and her Puerto Rican boyfriend, and gang fights between whites and Hispanic teens. Critics labeled Elvis Presley a sex maniac with his pouty lips, bedroom eyes, and swivel hips. Or maybe because he seemed to be having so much fun! [7] |

No Facilities and Dubious Critics |

Symphony Hall had no backstage facilities for women. The only other woman in the BSO, a harpist, offered to let Doriot change inside her harp's hard case. Doriot declined and asked for a proper dressing room. After some discussion, BSO management assigned one of the backstage rooms reserved for soloists to her. Newspapers reacted to Doriot's appointment with blaring headlines: “Woman Crashes Boston Symphony: Eyebrows Lifted as Miss Anthony sat at Famous Flutist’s Desk” Boston Globe, 10/12/1952 Another said: “Flutist, 30 and Pretty, Here with Boston Symphony” Springfield Morning Union, 10/10/1952. [4] Some offered fashion criticism. One noted that she dressed unobtrusively in a long sleeved, floor length black dress. Another said she “dressed well without aiming at spectacular effect, and her lipstick, though generously applied, is the right shade for her coloring.” Boston Globe 10/12/1952 |

Watch a video of Doriot and the BSO, conducted by Charles Munch in a stunning 1962 performance: "Danse generale" from Daphnis et Chloe - Suite No. 2 Wait for the end and watch Doriot get a solo bow! |

Reflections on critics and colleagues | Family TV: Wars and Rebellions |

Doriot later said: “I encountered more prejudice in the press than I did in the orchestra.” She had nothing but praise for her BSO colleagues: cellist Samuel Mayes, violist Joseph di Pasquale, French hornist James Stagliano, principal oboe Ralph Gomberg, principal bassoon Sherman Walt. [4]   During her 38 years with the BSO, Doriot won critical acclaim for performances under famed BSO conductors Charles Munch, Erich Leinsdorf, William Steinberg, Seiji Ozawa, and guest conductors Georg Solti and Pierre Boulez, many of them preserved on recordings. Many of Doriot's students at Boston University, New England Conservatory and the Tanglewood Music Center went on to orchestral careers: Geralyn Coticone (Solo Piccolo, BSO); Marianne Gedigian (Guest Principal Flutist, BSO, Principal Flutist of the Boston Pops); Toshiko Kohno (Principal Flute, National Symphony). [1] | Sponsored by makers of household products and targeted at homemakers, the first daytime soap operas appeared. The Guiding Light in 1952. In 1956 Irna Phillips created As the World Turns; the most successful daytime soap ever and the first to feature an illegitimate baby. [10] At night millions watched I Love Lucy, a sitcom starring Lucille Ball and her Cuban-born bandleader husband Desi Arnez. But even when she was pregnant, they slept in twin beds. Father Knows Best featured a wholesome white family: 2 parents, 2 kids. The Honeymooners, starred Jackie Gleason as a working class Brooklyn bus driver. The Korean War (1950 -- 1953) had ended, but fear of atomic bombs pronpted air raid drills in schools and cities. Nevertheless, by 1960, 60% of Americans owned their own home; 75% owned a car; and 87% owned a television set. [7] |

1963: The BSO Chamber Players |

In 1963 the Boston Symphony established the BSO Chamber Players, principal players of the string, woodwind, brass, and percussion sections. Doriot was the only woman. The Chamber Players concertized in Boston, New York City and at Tanglewood, toured the U.S. and abroad, and recorded for Nonesuch and Deutsche Gramophone. [3] At right: the BSO Chamber players in 1985. Doriot remains the lone woman. |   |

BLIND AUDITIONS In the 1960s, pressure from civil rights groups forced U.S. orchestras to hold more equitable auditions. By 1976, a third of the major orchestras used blind auditions for preliminary rounds; musicians played behind a curtain to hide their gender and/or ethnicity. This greatly increased the number of women and minorities hired. However, a screen was often not used for the final round. In 1998, 47 of the biggest orchestras used blind auditions for preliminary rounds.

In 1977 the BSO named Marylou Speaker [Churchill] principal second violin. That year 11 women held positions in the BSO—string players, and harp and flute—but none sat in the brass or percussion sections. In 1969, harpist Ann Hobson Pilot was the first African-American hired by the orchestra. In 1980 she was named principal harp. [2] | |

During the late 1980s Doriot toyed with the idea of retiring, but, reflecting upon her teacher William Kincaid, she said: “The Philadelphia Orchestra wind section all admired each other. And that’s one thing we did at the Boston Symphony.... I fell in love with our [woodwind] quartet ... that’s why I couldn’t leave the Symphony.” [1] At right: Doriot and three other principals of the BSO woodwind section: Sherman Walt, bassoon; Ralph Gomberg, oboe; Harold Wright, clarinet (1985). |   |

1990 Retirement When she did retire, she went out in style. The BSO commissioned Ellen Taafe Zwilich to compose a Concerto for Flute and Orchestra for her, which she premiered in April, 1990. The caption below a photo of her in the Boston Globe said: “Doriot Anthony Dwyer, a living legend of flute playing.” [4] Hear the 3rd movement “I love the piece,” Doriot said, “every note counts, and there are a lot of notes!” When asked how she maintained such high standards for so long, she said: “Music is like a fountain flowing with new challenges every day. That’s the reason I have never been bored.” [4] After leaving the BSO, she played recitals and recorded chamber music for Koch Records. In 1994 in a recital at Boston’s Gardner Museum, she and pianist Anthony di Bonaventura performed a piece composed for them by Charles Fussell. [6] Early in her BSO career, Doriot married and had a daughter, but she later divorced. At this writing, Doriot lives near her daughter in Kansas. |

COMMENTARY Legacy: At a time when women were almost non-existent in most U.S. orchestras, Doriot Anthony Dwyer worked tirelessly to achieve her goals. Because of her prodigious talent, steely determination and tireless effort, she became one of the top orchestral flutists in the world, as demonstrated by her recordings with the BSO, the BSO Chamber Players, and in solo recitals.

Role models, mentors, influences: Her most important role model was her mother, Edith Anthony. Her teachers included many greats of the flute world: William Kincaid, Ernest Liegle, Georges Barriere, and Georges Laurent, her predecessor in the BSO. Another influential teacher was oboist, Henri de Busscher. [4] She also studied ballet and voice, and often discussed phrasing with the great black tenor recitalist Roland Hayes. Conductors Bruno Walter and Charles Munch recognized her talent and defied convention to hire her as principal flute.

Gender issues: In 1991 Doriot spoke at Boston University forum in response to remarks made by BU trumpet professor Rolf Smedvig about a female student brass group. “In opera,” Doriot said, “women always had prominent roles; nobody ever said [they] sang well ‘for a woman.’ A woman can sing as loud as any man. Never have I heard a conductor urge a male instrumentalist to play in a ‘more feminine’ way. [If someone told] them to play more like a woman, it would be considered a putdown. But I have certainly heard women being told to play more like a man.” She contradicted Smedvig’s assertion that women don’t have the stamina to play heavy brass. “A soprano singing a major operatic role needs more stamina than any instrumentalist.” [5] |

Hear Doriot play the flute solo from Debussy Afternoon of a Faun, the BSO conducted by Leonard Bernstein Doriot-BSO-Bernstein DISCOGRAPHY Doriot Anthony Dwyer played on most of the BSO recordings made between 1952 and 1990. Listed here are a few examples of her many recordings with the BSO and chamber groups. A Debussy Weekend, compilation, 2006 Munch Conducts Berlioz, compilation boxed set, 2004 Chamber Music of James Yannatos, Albany Records, 2000 Ravel: Orchestral Works, Deuche Gramophone, 1995 Zwilich: Concerto for Flute and Orchestra/Piston: Concerto for Flute and Orchestra/Bernstein: Halil, Koch Records, 1994 Daniel Pinkham: Miracles, Diversions & Proverbs, 1983 The Boston Symphony Chamber Players, various works, 1970 |

SOURCES: 1. First Flute: The Pioneering Career of Doriot Anthony Dwyer, Kristen Elizabeth Kean, submitted in partial fulfillment of Doctoral Degree, LSU, 2007 2. Unsung: A History of Women in American Music, Christine Ammer, 2nd edition, 2001 3. Tanglewood 1985, Boston Symphony Orchestra publication 4. “A farewell to the BSO’s magisterial flute,” Richard Dyer, Boston Globe, 4/22/1990 5. “Of gender, bravado and brass: A trumpet star’s blare at female students stirs debate over stereotyping,” Richard Dyer, Boston Sunday Globe, 4/21/1991 6. “Doriot Anthony Dwyer still seeking out new challenges,” Richard Dyer, Boston Globe, 12/12/94 Fifties Sources:

7. Young, White, and Miserable: Growing Up Female in the Fifties, Wini Breines, 1992 8. On the Verge of Revolt: Women in American Films of the ‘50s, Brandon French, 1978 9. This Fabulous Century: 1950-1960, Time-Life Books, 1988 10. www.museum.tv/archives Soap Opera, accessed 6/27/2008 |

© copyright 2008 Susan Fleet