|

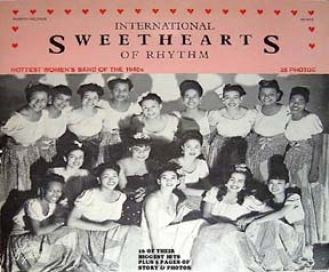

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm (1937 -- 1955) |   | Hear the Sweethearts play Don't Get It Twisted |

Bonus profiles: Four Sweetheart standouts! Photos: Left to right Vi Burnside, tenor sax, Pauline Braddy, drums Tiny Davis, trumpet, Carlene Ray, guitar |   |   |   |   |

1937: Birth of a Band

|

1937: Prices and Events |

The band originated at Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi, a boarding school founded by Lawrence C. Jones in 1909 to care for poor and orphaned black children. Aware that the Fisk Jubilee Singers raised money for Fisk University, Jones decided to do the same. In 1927 his Cotton Blossom Singers netted thousands of dollars for the school. [2, 5]

Pauline Braddy, the band drummer, attended the school as had her mother before her. “It was a gorgeous place,” she said, “and it did so much for so many poor blacks in the South. ... A kid could go to school and not have to pay anything. You worked your way and they taught you something.” [2] | Bread: .09/loaf Milk: .50/gallon Car: $675 Gas: .20/gallon Average Income: $1,789/year President: Franklin D. Roosevelt Hot new toy: Monopoly Top Songs: Goodnight My Love, Benny Goodman; Once in a While, Tommy Dorsey; The Moon Got in My Eyes, Bing Crosby Dorothy Fields was the first woman to win an Oscar for songwriting Top Books: Invincible Louisa: The Story of the Author of Little Women by Cornelia Meigs; Out of Africa, by Isak Dinesen |

In the 1930s, swing was king, popularized by the Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington and Count Basie bands. But several female bands proved women could swing too, most famously Ina Ray Hutton and her Melodears. |

After hearing Hutton's band in 1937, Jones decided to start one of his own. Fifteen girls, age 14 to 19, joined the Piney Woods School band. Some had played in the marching band; others were taught to play instruments by Consuella Carter, the school music teacher. “She was a great musician,” Braddy said. “She played cornet and led the band. We had records, but we weren’t supposed to have them, ‘cause it was a religious school. We used to hide them ... Count Basie and Andy Kirk and all the old black swing bands.” [2,5] Jones dubbed them The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, because some of his black students had a parent who was Asian, Hispanic, or Native American. |

1938 - 1939: Strict Rules and Student Hijinks

|

In 1938 they toured Mississippi, playing stock arrangements in dance halls. Jones hired Rae Lee Jones as chaperone, Vivian Crawford as tutor, trumpeter Edna Williams as music director. In 1939 the band toured Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee and Texas. [5] Chaperone Jones set down strict rules, but the teens chafed at the restrictions. “We used to sneak off and go places,” Braddy said. “One time [Emcee] Willie Bryant ran us out of the Elks’ Club. We had gotten our cigarettes and our rum and Coke—we didn’t know anything else to drink. The lights came on and he said: ‘Excuse me, ladies and gentlemen, I see some of my children.’ He put us in a cab to the Theresa Hotel, tipped the driver, and told him not to leave till we got on the elevator. And we were trying to be grownup! But ... we were a bunch of little nutty kids.” [5] |

1940 -- 1941: Smash Hits and Student Rebellions |

A smash-hit at their 1940 Howard Theater debut in Washington, D.C., they followed with a performance at New York’s Apollo Theater that had “all of Harlem talking.” The band played for mostly black audiences at clubs all over the U.S. When they returned to the Howard Theater in 1941 they broke box office records, drawing 35,000 patrons in a week. The band became the primary fundraiser for the school. [4,5] But there was, as the saying goes, “trouble in River City.” The band got good press, albeit mainly in black publications, and as more experienced players joined the band, better bookings. The band’s earnings soared, but the girls did not share in the rewards. They were paid $8.00/week, of which $7 went for food. [5] “We rehearsed quite a bit,” said baritone sax player Willie Mae Lee Wong. “We really didn’t think about the money—we just liked playing.” [2] The band was earning $3,000 a month for the Piney Woods School, but the girls feared they might not graduate. After the school bought life insurance policies for them, with the school as beneficiary, the girls rebelled. They wanted better salaries, graduation guaranteed, and the right to choose their own beneficiaries. When they threatened to strike if conditions did not improve, Jones fired the chaperone and tutor, and sent school officials to bring the rebellious musicians back to school. [5]

The girls severed their connection with the Piney Woods School and fled to Washington, D.C. [2] The Swinging Rays of Rhythm replaced them, but never achieved the fame of the Sweethearts, nor did it garner the same rave reviews. |

1941 -- 1942: New Directors, New Directions, Continued Exploitation |

At that time the American Federation of Musicians was segregated, so the girls joined Washington D.C.’s black local, and arranger Eddie Durham signed on as bandleader. Formerly a trombonist with Count Basie, he had arranged for Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw and Ina Ray Hutton. “We started [rehearsing] at ten in the morning,” Durham recalled, “and quit at nine at night. [I] taught ‘em a little choreography with their horns, not dancing, but how to come in with their horns and do things.” [5] The choreography included spectacular lighting and fabulous gowns. “We had seven different gowns,” Pauline Braddy recalled, “and seven different pairs of slippers that went with the gowns, and you weren’t seen onstage until you were just so.” [2] After the U.S. entered WW II in 1941, all-women bands were in demand because male musicians were being drafted. There were other black women bands—the Harlem Rhythm Girls, the Prairie View Co-Eds—and white women bands—Ada Leonard’s All American Girl Orchestra and Babe Egan's Hollywood Redheads to name a few—but none played hard-driving swing like the Sweethearts. |

Here's a 1946 video of ISR Anne Mae Winburn, leader/vocalist; Vi Burnside plays tenor sax solos on She's Crazy With The Heat; Do You Wanna Jump Children? and How 'Bout That Jive? Tiny Davis does the vocal and plays trumpet on Round & Brown Blues (sound out of sync) |

When not on tour, the Sweethearts lived in a 10-room house in Arlington, VA. By then they were bringing in good money, but the financial exploitation continued. “They paid the girls thirty-two dollars a week,” Durham said, “and told them the rest went to pay for the bus and the house in Arlington.” But Durham knew the band backers owned the house. Angry that the men took so much money and paid the women so little, Durham quit the band. | |

Jesse Stone was hired as director-arranger. [2] A fine pianist, arranger and composer, Stone gave the band a new sound, featuring vocal and instrumental specialties. Glamorous Anna Mae Winburn, who had fronted several male bands, joined the band, as did other seasoned professionals like sax player Vi Burnside and trumpeter Tiny Davis. [2,5] In 1942 the band made two coast-to-coast bus tours. Stone booked them on a tour with Fletcher Henderson’s band. The groups alternated sets, combining on a 35-piece combined finale. |   |

1943 -- 1944: Dangerous Travels in the South with Jim Crow | |

On tour the women ate and slept in a live-in bus. Not only was it cheaper, segregation laws prevented them from entering white hotels and restaurants. Trumpeter Toby Butler and alto sax player Roz Cron (pictured at right in the ISR saxophone section standing beside Vi Burnside) joined the band in 1943 and 1944, respectively, a notable change since both were white. [5] |   |

Some of the lighter-skinned Sweethearts wore dark makeup lest policemen suspect they were white. Butler and Cron did the same. When asked, they said that their mothers or fathers were black. [5] “We dared to travel through the South in the ‘40s,” said singer Evelyn McGee. “One time in Miami ... those cops shook their heads. They knew some of the players were white. ... This was unheard of in those days, but we got away with it.” [6] Sometimes with narrow escapes. White alto sax player Roz Cron recalled an instance where they were warned that the cops were coming to arrest them. “A cab driver spirited us out of town,” she said, “while we lay on the floor of the cab.” [6] Exploitation of the players continued. They were paid far below union scale, told they owned the Arlington house [they didn’t], and that Social Security had been deducted from their pay. It had, but the money was never paid into Social Security. | Life on the road was dangerous in the South. Jim Crow laws divided people into two separate and unequal categories: white and colored. Whiteness was defined as pure and superior and fiercely protected; colored meant anyone with black ancestry, including people of color who were not African-American. Anyone of mixed race was deemed colored. Laws prohibited blacks and whites from performing, traveling or living together. White women onstage with black women was unacceptable. White supremacists hated the fact that black men in the audience were watching white women, a cause for lynchings. [3] |

Band leader Jesse Stone eventually left the band over these issues. “In Baltimore, Maryland,” he said, “the girls played five shows a day over a holiday weekend. Christmas. And the girls were paid $50 apiece. I couldn’t stand it. [He and the managers] had a big argument and I gave my notice. They begged me to stay but I gave two weeks notice and quit.” [6] |

1945: A USO Tour for Segregated Troops |

The new music director was Maurice King. The band's fame grew in 1945 when they played for Armed Forces Jubilee Programs broadcast over short-wave radio to troops overseas. Black troops—The US military was not desegregated until 1949—sent requests for the Sweethearts to appear at their camps. At Rt: band members in their USO uniforms. In July, they sailed for Europe with director Maurice King. Europe loved the Sweethearts and the Sweethearts loved Europe. They played two shows a day at camps in France and Germany, primarily for white U.S. soldiers. Black troops were seated separately. King made sure the women received their pay directly from the USO. The women came home with more money than any of them had ever seen before. [5] |   |

Clip from 1940s ARMED FORCES RADIO, ISR plays Lady Be Good, features drummer Pauline Braddy |

1946 -- 1949: The Band's Last Years |

Upon their return to the States, several women left the band and others, like guitarist Carlene Ray and bassist Edna Smith joined it. By 1947 key players Tiny Davis, Vi Burnside and Anna Mae Winburn had left the band. Chaperone Rae Lee Jones died, and in 1949 the band broke up. The Sweetheart House in Arlington was sold, but, although their earnings had been used to finance the house, band members received no money from the sale. [5] |

1950 -- 1955: Sweetheart Spinoffs |

Anna Mae Winburn reorganized the band in 1950, calling it Anna Mae Winburn and her Sweethearts of Rhythm. The band grossed $52,000 in six months, but disbanded five years later. Rock and roll was sweeping the country, television brought free entertainment to millions of homes, and swing bands—male and female—were out of favor. Rt: Anna Mae Winburn & the Sweethearts |   |

FOUR SWEETHEART STANDOUTS Vi Burnside, sax -- Pauline Braddy, drums -- Tiny Davis, trumpet -- Carlene Ray, guitar |

Violet "Vi" Burnside: tenor saxophone (dates unknown) Little is known about the early training of sax soloist Vi Burnside. During the 1930s she emerged as a major talent, admired for her vigorous, swinging style in the tradition of Ben Webster and Coleman Hawkins. [1] Her solo on “Sweet Georgia Brown” recorded at a break-neck tempo with the Sweethearts demonstrates her hard-driving swing technique. [2] A featured soloist with the Harlem Playgirls in the 1930s, she played a similar role with Sweethearts until the mid-40s, continuing her career in the 1950s in Washington, D.C. where she led small groups and was active in the union. |   |

Tenor sax player Willene Barton said, “Vi Burnside opened the door for the rest of us. After the Sweethearts broke up, every manager in New York was after Vi Burnside. I have never seen a woman command that kind of attention. She showed up [all over] America. When she made her debut at the Baby Grand in Harlem, you couldn’t get near the door.” [1] In the photo at right: Vi Burnside stands at left, Anna Mae Winburn on piano, and trumpeter Tiny Davis entertain some young fans |   |

Pauline Braddy, drums (dates unknown) Braddy grew up at the Piney Woods School and played clarinet in the brass band. “I got the drums by accident,” she said. Her heart was set on the alto sax, but “they said I had a good sense of rhythm. They said ‘Pauline’s a natural.’ I cried. Who wanted to play the drums? So, I was stuck with it, really.” [2] But she played well enough to draw attention from drummer Sid Catlett, who played with Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie drummer Papa Jo Jones. Pauline Braddy playing drums at right. |

|

During the mid-40s when the Sweethearts were at their peak, a quartet from the band recorded Stone’s arrangement of “Blue Skies,” Pauline Braddy played a drum solo on her specialty: Drum Fantasy. “It was fabulous,” she said. “You painted your sticks with fluorescent stuff and the cymbals and the rims and then they put on black light. I played with white gloves. It broke up the [audience] all the time.” [2] | |

After the 1945 USO tour, Braddy stuck with the band until the 50s, then quit. Five years later she came out of retirement to play in a trio with Edna Smith and Carlene Ray in New York. In the late 60s she played with Vi Burnside’s group in Washington. D. C. Photo at right: (Braddy at left, with Flo Dryer, trumpet; Vi Burnside, sax; unidentified bass and pianist). In 1980 Braddy came out of retirement for the Women’s Jazz Festival in Kansas City to play in a tribute to the Sweethearts. |   |

Ernestine “Tiny” Davis: trumpet and vocals (1907 – 1994)

Davis grew up in Memphis. At 13, after hearing the trumpets in the school band, she asked her mother for one. She got her only instruction in school and practiced “two or three hours a day.” Later, Louis Armstrong became her biggest influence; she would listen to his records and play along with them. [2] Photo of Tiny Davis at right |

|

She moved to Kansas City, then a hotspot of jazz, played in nightclubs for “two dollars a night” and listened to other musicians around town. During the mid-1930s, she toured with the Harlem Playgirls. In 1941 Jesse Stone recruited her for the Sweethearts. Nicknamed “Tiny” because of her large size, she became a feature attraction, singing and playing trumpet with them for almost 10 years. In 1947 she left the band to form her own group, Tiny Davis and her Hell Divers (photo below) | |

They played the Apollo and other New York clubs. After touring Puerto Rico, Jamaica and Trinidad, she settled in Chicago and kept on playing. “Never done nothin’ else but blow the trumpet," she said. [2] She and her partner Ruby Lucas owned Tiny and Ruby’s Gay Spot in Chicago during the '50s. Tiny & Ruby: Hell Divin’ Women, a 1988 film about them directed by Greta Schiller and Andrea Weiss won Best Documentary at the San Francisco Film & Video Festival. Watch a Clip of Tiny & Ruby film |   |

Carlene Ray: guitar, bass, piano, vocals (1925 -- 2013) Born in 1925 in Manhattan, Carlene Ray grew up hearing all kinds of music. Elisha Ray, her father, was a Tuskegee graduate, and earned a music degree from Julliard the year Carlene was born. During WW I, he had played with the famed 369th Infantry Band led by James Reese Europe. “Walter Damrosch asked him to join the brass section of the NY Philharmonic,” Carlene said, “but he needed more substantial employment; at that time the Philharmonic didn’t play year-round, only a few weeks of the year.” So he went to work for the Postal Service. [2] |   |

However he continued to play music and began taking Carlene to rehearsals when she was three. She also listened to the radio. “I had a good ear,” she said, "but I couldn’t read [music] until junior high school.” [2] In 1941 she entered Julliard at 16 and stayed five years, after changing her major from piano to composition. She began working with jazz bassist, Edna Smith. playing piano and rhythm guitar. After graduating in 1946 she joined the Sweethearts on rhythm guitar and vocals. |   |

In 1948 she sang for Erskine Hawkins’ band on the black theater circuit. She married bandleader Luis Russell, who had helped organize a group led by Louis Armstrong, but continued to perform even after their daughter, Catherine, was born. Carlene often took her daughter to recording sessions and performances. Mr. Russell died when Catherine was 7. Carlene spent decades as a session musician, playing electric Fender bass at studios in New York. She sang classical choral works including performances conducted by Leonard Bernstein. She also sang backup on recordings for Pattie Page, Bobby Darin, and many others. | |

In 1956 she earned a master’s in voice from the Manhattan School of Music. During the 60s and 70s, Carlene played with the bands of Mary Lou Williams, Mercer Ellington, and Melba Liston. From 1969 to 1979 she toured extensively with the Skitch Henderson band. Carene Ray died July 18, 2013. The headline on her obituary in the New York Times was Carline Ray, an Enduring Pioneer Woman of Jazz, dies at 88. |   |

COMMENTARY ROLE MODELS: Few female role models existed in the '30s and '40s. “There was no one to look up to,” said Pauline Braddy. "I just wanted to play. I never thought that there weren’t many girls that played.” Nor did she think of a music career. “In those days ... you didn’t have any idea of what was a career or what you wanted to do." [2]

MALE MENTORS: In addition to leaders Durham, Stone and King, Leonard Feather, jazz promoter, critic and record producer, actively sought out, recorded and interviewed women players and singers. Frank Driggs, whose collection of jazz photos includes many jazzwomen, published a booklet in 1977: Women in Jazz: A Survey. [1] GENDER BIAS: Consider the terminology. “All-girl” was the term used for women’s groups; but male bands weren't called “all-boy” bands. Similarly, many referred (pejoratively) to the women in the bands as “a bunch of dykes.” But all-male bands were not described as “a bunch of queers” or other such derogatary terms. Pauline Braddy recalled an attitude that women “should stay home and learn to cook and all that kind of stuff. Even the musicians union didn’t change the heading of their letters; it was always “Dear Brother” or Dear Sir.” Kind of insulting, I thought.” [2] Articles during the '30s and '40s in Down Beat magazine with titles like "Why Women Musicians Are Inferior" didn't help. [6]

Vibraphonist Marjorie Hyams, who played with Woody Herman’s First Herd (1944-45) summed it up best: “You weren’t really looked upon as a musician ... There was more interest in what you were wearing or how your hair was fixed—they just wanted you to look attractive, ultra-feminine, largely because you were doing something they didn’t consider feminine.” Hyams insisted on wearing the band uniform, not a dress. [1] But by the '80s things had improved. In 1982 Carlene Ray said: [In the past] “a lot of women weren’t taken seriously ... now they’re beginning to take women seriously, but I would just rather be taken seriously as a musician, and the fact that I’m a female—I just happen to be female, that’s all.” [2] RACIAL DISCRIMINATION: Pauline Braddy: “The [Sweethearts were] enormously popular with blacks, but hardly known by whites.” [2] Most of the women's bands covered by the white media were white groups. Ina Ray Hutton and Her Melodears and Phil Spitalney’s All Girl String Orchestra gained fame because they made films and records. Spitalney’s group had a weekly radio show, The Hour of Charm, for fifteen years. It's almost impossible to find recordings of black women's bands other than the Sweethearts, and although the Sweethearts appeared in a few short films, these films were directed at black audiences; none were shown in the South. GENDERED INSTRUMENTS: For centuries it was okay for women to sing. In the late 19th century, they were even encouraged to play piano as a social skill. But other instruments were off limits. As trumpeter Clora Bryant put it: “If you sing or play piano, you get more gigs.”[6] Drums, trumpet and trombone were considered “masculine.” Others, like flute, violin and clarinet, were considered “feminine.” Women were discouraged from playing instruments considered “too large” for them, like string bass or tuba. And there has been, until recently, a long-held assumption that jazz is a “man’s music.” During the 1980s and '90s jazz improvisation began to be taught in high schools and colleges. Prior to that, it had to be learned in venues considered unseemly, even dangerous for girls. The SWEETHEARTS LEGACY is preserved in recordings and films (Discography below), and the documented words of band members. For example, bandleader Jesse Stone said fans waited in the rain outside Detroit’s Paradise Theater for a week to hear the band. “I never saw them do that for Duke Ellington,” he said, “I really didn’t.” [2] A wave of feminism during the 1970s generated new interest in women jazz players and all-woman bands; see Sources below for books published about them in the early 1980s. 1980: A Salute to the International Sweethearts of Rhythm was part of the Third Women’s Jazz Festival in Kansas City. Fifteen Sweethearts attended. 1984: Rosetta Reitz issued an LP of the Sweethearts’ records, including cuts from their 1945 Armed Forces Jubilee radio broadcasts. 2000: Sherrie Tucker interviewed women who played in many all-women bands and published Swing Shift: "All-Girl" Bands of the 1940s 2004: the Kit McClure Band released The Sweethearts Project (Redhot Records), a tribute album recorded with an all-female band using songs the Sweethearts recorded. |

Hear four songs on a 1946 video of ISR: Anne Mae Winburn, leader/vocalist; Vi Burnside plays tenor sax solos on She's Crazy With The Heat; Do You Wanna Jump Children? and How 'Bout That Jive? Tiny Davis does the vocal and plays trumpet on Round & Brown Blues (sound out of sync) Watch a clip of documentary about Davis DISCOGRAPHY International Sweethearts of Rhythm: Hottest Women’s Band of the 1940s, Rosetta Records RR 1312; Hot Licks 1944-1946, DSOY692: a compilation of some of their live radio appearances Forty Years of Women in Jazz: A Double Disc Feminist Retrospective, Jass CD -9/10, includes four cuts of the band Short films: The International Sweethearts of Rhythm (1947); That Man of Mine (1947); Harlem Carnival (1949); Harlem Jam Session (1949); Jazz Women on Video (1932-1952): Foremothers, Vol. 1, includes a cut of the Sweethearts, Rosetta Records, RRV 1320 |

SOURCES: 1. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen, Linda Dahl, 1984 2. Jazzwomen: 1900 to the Present, Their Words, Lives and Music, Sally Placksin, 1985

3. Swing Shift: “All-Girl” Bands of the 1940s, Sherrie Tucker, 2000

4. The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, D. Antoinette Handy, 1983.

5. Record liner notes, Rosetta Reitz: International Sweethearts of Rhythm, Rosetta Records 1984

6. All Women Bands of the ‘20s, 30s, and 40s, a PBS radio program produced by Margo Stage and Sally Placksin 7. Carline Ray, an Enduring Pioneer Woman of Jazz, Dies at 88, by William Yardley, New York Times, July 27, 2013 |

© copyright 2008 Susan Fleet