Maud Powell 1867 -- 1920 Pioneer concert violinist First solo instrumentalist to record for RCA Victor Red Seal Her records were international bestsellers. At right: child prodigy Maud Powell plays violin Far right: Nicolas R. Brewer 1918 oil portrait of Maud |   |   |

MAUD POWELL 1867 -- 1884 Life on the Frontier | 1867 -- 1884 News and Events |

Three years after the Civil War ended in 1864, Maud was born in Peru, Illinois. Her father, William Bramwell Powell, an innovative educator, was superintendent of public schools in Peru. Her mother, Minnie Paul Powell, was a talented pianist and composer, but in those days, most women stayed home to raise a family; they didn't have professional music careers. Maud's uncle, John Wesley Powell, headed the U.S. Geological Survey and founded the National Geographic Society. [1] When Maud was 3, Mr. Powell moved the family to Aurora, Illinois, to begin his new job as public school superintendent. Four years later, at age 7, Maud began violin lessons. At 9, she began four years of study with William Lewis in Chicago, traveling there by train once a week. Lewis recognized her talent and sometimes had her play duets with him in recital. She became a celebrity in Aurora, performing with local musical groups, including Stein’s Orchestra. In 1880 her first solo performance with the orchestra was deemed “one of the wonders of the age.” [3] Although many people felt it was unseemly for a girl to study violin, Maud persevered. Her idol was renowned French violinist Camilla Urso (1842-1902) whom she had heard play in 1875. She dreamed of becoming a celebrated violin soloist. Recognizing her prodigious talent, the Powells sold their home to finance her continued education. In those days this meant studying with the great teachers in Europe. | President Andrew Johnson [Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated in 1964] Nebraska became the 37th state. The United States purchased Alaska from Russia for $72 million. 1870 population: 39.8 million, including 4.9 million African Americans. Blacks voted for the first time in a state election in the South (Tennessee); Fisk University, an all-black college, was established Popular books: Louisa May Alcott, Little Women (1868); Horatio Alger, Ragged Dick series (1867); Mark Twain, (Samuel Clemens) The Innocents Abroad (1869) Music premiers: Johannes Brahms German Requiem (1868); Max Bruch, Violin Concerto in G Minor (1868); Tchaikovsky, Overture to Romeo and Juliet (1869) |

In 1880, at the age of 13, Maud, accompanied by her mother and brother, went to Germany, hoping to study with celebrated violinist Joseph Joachim. After hearing her play, he accepted her as his pupil. While in Europe Maude also studied with Henry Schradieck (Leipzig) and Charles Dancia (Paris). Photo at right: Maud in 1880 She made her professional debut with the Berlin Philharmonic, playing the Bruch Violin Concerto [4]. In 1884, at the age of 18, Maud returned to the United States, determined to launch a solo career. [1] |   |

MAUD POWELL 1885 - 1903 True Grit

| 1885 – 1903 |

Knowing that “girl violinists were looked upon with suspicion,” Maud boldly walked into a rehearsal of the all-male New York Philharmonic. She demanded a hearing from Theodore Thomas, then America’s foremost conductor, and blew him away with her talent. [1] Deeming her his “musical grandchild,” Thomas hired her to play the Bruch G Minor violin concerto with the orchestra. Of her performance on November 4, 1885, NY music critic Henry Krehbiel said: “She is a marvelously gifted woman, one who in every feature of her playing discloses the instincts and gifts of a born artist.” [1] At that time there were no established concert circuits, and solo engagements were difficult to obtain, especially for a woman. Only five professional orchestras existed in the U.S., all-male with male conductors. Establishing a career in Europe might have been easier, but Maud chose to stay in the U.S. Her mission: bring classical music to Americans, not just in large cities, but in remote areas as well. Braving primitive conditions, she pioneered the violin recital in concerts throughout the country, reaching people who had never before heard classical music. In 1891 she toured with the Patrick Gilmore Band in 75 concerts, and with the John Philip Sousa Band in 1898. [4] She played concertos and sonatas, educating audiences with her program notes and with journal articles about the history of violin playing. She played special programs for children and advised aspiring musicians of both genders. [2] | Patent medicines were available for all sorts of ailments; many contained drugs or alcohol. Lydia Pinkham marketed a medicine for female ailments, which grossed $300,000 in 1883. By 1890 the greatest migration in U.S. history had increased the population west of the Mississippi from less than 7 million to more than 16 million. Total population rose from 39 million to 63 million. The 10 largest cities were New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Boston, Baltimore, San Francisco, Cincinnati, New Orleans, Pittsburgh. Carriages and horse trams clogged city streets. By 1888, electric trolleys were running in several cities. With no radio or TV and few recordings, people attended live performances in urban theaters or tents in rural towns to see traveling circuses and variety shows that featured songs, dances, comedy skits and specialty acts. In 1900, 8000 cars were registered in the U.S. In 1901, Orville and Wilber Wright experimented with flying machines. |

In 1893 Theodore Thomas chose Maud to represent America’s achievement in violin performance at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, known as the Chicago Worlds Fair. Maud was the only female violinist to perform. While there, she presented a paper to the Women’s Musical Congress, “Women and the Violin,” which encouraged girls with musical talent to take up the violin seriously and women of all ages to form music clubs and orchestras across the U.S.

Photo at right: Maud Powell, c. 1891 At that time, women could not vote in national elections nor play in a professional orchestra. Women were not admitted to the American Federation of Musicians until 1903. However, Maud insisted that there was no reason why women could not play violin with the best of men. [1] |   |

In 1903 Maud toured Europe with the John Philiip Sousa band and began a relationship with the band manager, H. Godfry "Sunny" Turner. Photo at right. In 1904, against the wishes of Maud's mother, they were married. Maud's parents did not attend the wedding. [4] Only years later did Maud and Sonny reconcile with her parents. |

|

1904 -- 1919 New technology and wider fame |

In 1904, The Victor Company selected Maud to be their first solo instrumentalist to record for a new celebrity artist series (Red Seal). In an historic marriage of recording technology and high quality violin playing, Maud stood before a large funnel to perform. Her music’s vibrations agitated a needle in an adjoining room that scratched impressions of sound waves on the soft, spinning wax from which a record could then be molded. [1] Photo at right: Maud Powell autographs records |   |

“I’m never as frightened as when I stand in front of that horn to play,” Maud said. “There’s a ghastly feeling that you’re playing for all the world and an awful sense that what is done is done.” [1] There were no cuts and splices in those days. Pieces were played from beginning to end without pause. Electrical recording with microphones did not begin until 1925, after Maud’s death. However, her recordings set the standard for violin performance and became world-wide best sellers. [2] Her recorded legacy demonstrates why her name stands alongside those of Caruso, Melba, Kreisler and Paderewski as one of the “Victor Immortals.” [1] Photo right: Maud Powell, 1916

|

|

Perhaps her greatest artistic triumph was her 1906 premier of the Sibelius Violin Concerto, which she called “a gigantic rugged thing, an epic really ... Oh, it is wonderful.” [1] Although the piece was initially rejected by critics (“... why did she put all that magnificent art into this sour and crabbed concerto?”), the Sibelius Violin Concerto is now one of the most recorded violin concertos. [1] Maud played the American premiers of violin concerti by Tchaikovsky, Dvorak, Sibelius, Saint-Saëns, Bruch, and many others. She championed the works of American composers Amy Beach, Victor Herbert, Cecil Burleigh, Arthur Foote, Grace White and many others. She also chose promising young pianists to accompany her in concert and recordings, including Arthur Loesser, Francis Moore, and Axel Skjerne, paving the way for their solo careers. | ||

1920 MAUD'S CLOSING CHORD | ||

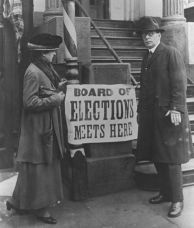

After a period of failing health and heart problems, Maud felt well enough to cast her vote in 1919. At right: Maud and Sonny outside a New York City polling place Far right: Maud casts her vote |

|

|

The following year, she resumed her concert tours. But while rehearsing for a concert in Uniontown, PA, Maud suffered a heart attack. She died the next day on January 8, 1920, at the age of 52. The New York Symphony paid tribute to this “supreme and unforgettable artist. She was not only America’s great master of the violin, but a woman of lofty purpose and noble achievement, whose life and art brought to countless thousands inspiration for the good and the beautiful.” [1] A statue of Maud stands in her hometown of Peru, IL, which holds an annual Maud Powell Music Festival. Thanks to Karen Shaffer, Maud Powell biographer and president of the Maud Powell Society for Music and Education, the Maud Powell legacy endures. An online magazine is published on their website. See tthe Maud Powell Website. | ||

For a comprehensive Maud Powell biography, including many photographs, see WOMEN WHO DARED: Maud Powell and Edna White | ||

COMMENTARY |

A passion for music. Even as a child, Maud had a passion for music. At an early age, she demonstrated great determination, a capacity for hard work and above all, prodigious musical talents. Fortunately, her parents recognized this and encouraged her. OBSTACLES: Although Maud Powell believed that women violinists could have professional careers, during her lifetime (1867-1920) professional orchestras were all-male. Women had to play in all-female groups, most of them unpaid. A year before her death in 1920 Maud admitted: "When I first began my career as a concert violinist ... a strong prejudice then existed against women fiddlers, which even yet has not althogether been overcome." [4, 1] Not until orchestral auditions were held behind screens to conceal their gender in the 1970s did women begin to win orchestral positions in large numbers.

ROLE MODELS and MENTORS: Maud Powell had few female violinists to emulate. Her early idol was concert violinist Camilla Urso. Maud's talents were championed by Theodore Thomas and other male conductors won over by her astounding virtuosity and musicianship. MAUD POWELL'S LEGACY: Internationally recognized during her lifetime as America’s greatest violinist, Maud ranked among the best violinists of her day: Joseph Joachim, Eugene Ysaye and Fritz Kreisler. Combining her European training with her American spirit, she proved that a woman could play violin as well as a man and set a enduring standards for virtuosity and musicianship. She led her own Trio (1908-09) and Quartet (1894-1898). Her American premiers of the Tchaikovsky, Dvorak and Sibelius violin concertos helped advance violin technique into the modern age. She toured the US, Europe and South Africa to wide acclaim, appearing with great orchestras under such famed conductors as Joachim, Mahler, Nikisch, Thomas, Damrosch, Richter, Wood, Herbert, and Stokowsky. [2]

|

DISCOGRAPHY Maud Powell recordings reissued on CD: MAUD POWELL—Complete recordings Vol. 1, 2 and 3, [Naxos] works by J.S. Bach, Beethoven, Bruch, Elgar, G.F. Handel, Felix Mendelssohn, Pablo Sarasate, and Henryk Wieniawski. Her Victor catalog includes dozens of recordings (1904 –1916); See: victor.library.ucsb.edu/talent Violinist Rachel Barton Pine plays concerts in honor of Powell. See amazon.com for her recordings. |

SOURCES 1. “Maud Powell, A Pioneer’s Legacy,” Karen A. Shaffer, in The Maud Powell Signature Women in Music, Vol. 1, No. 1, Summer 1995 2. “Maud Powell, Violinist,” www.foxvalleyarts.org 3. “Violin Genius Maud Powell: The Life and Work of a Celebrated American,” http://classicalmusic.suite101.com 4. Unsung: A History of Women in American Music, Christine Ammer, 2nd ed, 2001 |

© copyright 2009 Susan Fleet